So, let's start by explaining the basic ability of an XC pilot: handling flows. The difficulty is that the air is not visible. A paraglider can perceive it only “by touch” - by the way, his light wing throws from side to side. At the same time, a flight, especially a flight in a flow, is so unlike what happens to us in ordinary life that most people are unable to immediately find the optimal algorithm of actions. There are no analogies, all for the first time.

Once upon a time I was hanging out at Yutse and one experienced pilot, while we were waiting for the weather, told me a few words that contained all the wisdom of processing the stream. He said there was nothing complicated about it. You just need to apply the algorithm for finding the maximum value of the function - something like the Newton method, if you understand what I mean. We evaluate the rate of climb, and based on this we decide where to turn next. Naturally, not everything is simple here - the paraglider cannot turn around instantly, we should not, during our searches, move away from the lifting zone, otherwise, we’ll merge the entire height. However, some simple rules can even be driven into the machine, and then he will twist the threads. Below I will try to state these rules.

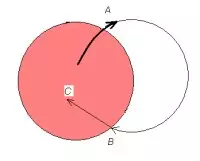

Imagine you are in a flow. Maybe you are flying in a straight line, or maybe you are standing in a spiral - this is not important yet. While you are steadily raising you, everything is fine - continue in the same vein. But then you felt a drawdown, and the device lowered its tone. What to do? Take a look at the drawing.

If so, then you are somewhere at point A. Indeed, you were in the stream, and then the rise decreased - that means you are falling out of the stream. What to do? No panic! We act in the following simple way: first, you need to increase the turn (hold the paraglider with an external brake if it lowers the air intake and drains very much). Then you have to do a little trick: wait until you turn around 3/4 of a full turn. After that, you will find yourself on the edge of the stream, and even in the “face to the core” position (point B). At this point, you need to align the roll and stretch. Even if by this moment the rise has not yet been felt, it will take 2-3 seconds, and you will be stuck in the very core (point C).

The difficulty is to correctly calculate these degrees of rotation. Beginning pilots look at the wing, at the instruments, and often completely lose their orientation. One must constantly cast glances left to right. This is useful when flying in a group, when flying on a slope, and is also necessary for proper flow handling. Keep in mind your direction all the time, as well as how much remains to turn around before the maneuver is completed. It’s convenient to get attached to some kind of landmark on the terrain, and always remember how you are located relative to it. The reference may be the top of the mountain, the direction to the starting point, the direction of the road along which you fly, or any other noticeable element of the surrounding landscape. In some glider book, I read the advice to navigate relative to the sun - I never did it myself, but why not? In addition to orienting about the terrain, try to imagine where the core is located at the moment from which you are thrown. A second ago, when the pros turned into minuses, the core was somewhere behind. You made part of the turn - where is the core now?

The question arises: here we stretched out and ended up at point C. What to do next? And how much does it stretch? I explain. You need to stretch until the rise stops growing. At this point, you need to spin, and harder. However, the moment of termination of growth is easy to miss, and indeed, who knows, can growth continue in a second? But in fact, you can expect a turbulent minus on the leeward side. In order not to fall into these minuses, it is recommended to remember the approximate radius of the stream, which is expressed in how many seconds you cross it. At point B, start the countdown, and after half the duration of the flight “from end to end”, spin into the core.

There is another option to continue the flight after point B: fly in a straight line or with a slight turn until you get to the minus. Then proceed according to plan A. This option is worse since the paraglider is being shaken at the flow boundary, the set is slower. However, this way you can determine the size of the thermal and its maximum rise. It happens that the pilot turns +1.5 on the edge, and nearby is +3 - you just need to stretch it in the right direction.

A small remark about how much you need to turn, falling out of the stream. It may seem that you need to rotate 180 degrees, half a turn. I still recommend turning three-quarters of a turn. If you just turn 180 degrees, you will most likely fly past the stream: during the turn, the paraglider is shifted to the side.

I will formulate once again the formula for processing the thermal flow, which is obtained from the above reasoning:

1) As long as the lift remains, continue to spiral with the same radius.

2) The rise disappeared or decreased - we turn on the algorithm for returning to the core:

1. With maximum intensity, we perform a 270-degree turn (3/4 turn).

2. We fly in a straight line - in a few seconds you will enter the core.

3) Once in the core, you need to stand in a spiral with the smallest radius that is most comfortable for you. If the rate of climb does not change during a full revolution, you have centered the flow correctly. If it changes, turn on algorithm 2 at the time of the rate of climb. At the time of the rate of climb, fly in a straight line or with a large turning radius.

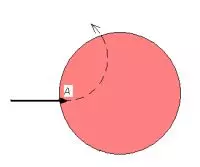

How to enter the stream

Imagine that you were at point A. At the same time, you will feel the rise, and the variometer will happily beep. An inexperienced pilot immediately begins to twist. It moves along a dashed trajectory, which, after half a turn, takes it out of the stream. At the exit of the stream, the paraglider dives. The pilot tries to spin harder to get back into the stream. But he forgets to keep the dome from going into a too-steep spiral. The decrease is growing, the pilot loses everything that he scored in half a turn in the stream, and another ten meters. What to do? For the first few seconds, you need to fly in a straight line. If you requested a flow in 1-2 seconds, you still cannot process it. That is, it does not make sense to twist in the first 1-2 seconds - you will not process a narrow stream, but in a wide one you will be off the edge. If you assume that the flow is narrow, it makes sense to spin on the third or fourth second after you (and the variometer) feel the rise. However, sometimes it makes sense to fly in a straight line and longer. For example, if you fly under a good cloud, look for a stream with a +4 core. There is no point in twisting when you see +1 on the device. Fly right to the center of the cloud, and the vario will start showing +1.5 first, then +2, then +3, and +4.

Twist as soon as the readings of the device stop growing. True, in turbulent weather, it happens that the pilot feels like the lifting has stopped, and twists, but it's too late. The dome falls out of the stream, the outer console - in the area of the downflows. Asymmetry. What to do in this case, is read the manuals for exiting extreme modes. However, if you are going to fly routes, asymmetries should not scare you. And how to return to the stream after falling out of it, I already wrote.

The question arises: which way to turn when you enter the stream? They say that you need to feel on which side it lifts stronger and turn there. I very rarely feel that on one side, the rise is stronger than on the other. Moreover, at competitions, pilots are obliged to twist in the launch area the spiral that was announced at the briefing: today is left, tomorrow is right. In general, it seems to me that in most cases the direction of the spiral is not important. If you feel in which direction the rise is greater - turn there. No - turn where you like best. Even if it turns out that you missed the core significantly - everything can be fixed by completing and stretching in time, as I described above.

One more remark - about streams and wind. I will say this: over the plain, or even far from the relief - forget about the wind. Handle the flow in the same way as in calm weather. According to Newton’s first law, a uniformly rectilinear blowing wind does not affect the behavior of the paraglider and the thermal. Some paragliders here doubt it - I want to dispel doubts, this is indeed so. The only thing you need to keep track of is your position relative to the land - is it taking you to a forest or a river? If the wind is strong and the stream is so weak that you are not gaining in it, maybe it makes sense to sit down at the start and try again. An alternative - while you fight, it will take you 5 kilometers, where you sit. Experience shows that it will be difficult to return. Even in the fields, there are insurmountable ditches with water, but nothing to say about the forest and other rough terrain.